Last Updated on July 9, 2022, 9:44 am ET

A recent qualitative study by the Coalition of Urban Serving Universities (USU) and the Association of Public and Land-grant Universities (APLU) observed, “universities are still designed for the college student of yesterday: enrolled full time, financially dependent on their parents, with no significant responsibilities of their own.” The study went on to illustrate how, for the most part, higher education is not designed to meet the basic needs of students today, who are more likely to be working adults, come from low-income households, or to be the first in their family to attend college.

This impact story describes some of the barriers to academic success that students increasingly face due to increases in tuition, rising costs of living, and the decreased purchasing power of federal student benefits. Many Association of Research Libraries (ARL) member libraries are part of affordable-learning initiatives at their institutions, and are involved in developing open educational resources (OER). Here, the focus is on the systemic problems that affect students and their families, and the broader policy opportunities to support students as the US Congress and the Biden-Harris administration plan for an unprecedented investment in social policy. ARL’s Advocacy and Public Policy Committee will track and monitor these investments as part of the Association’s commitment to advancing access to economic and social prosperity, and encouraging full participation in society. This commitment means supporting access to knowledge for all students, including undergraduate and graduate students experiencing additional economic strain because they are supporting families, students with unstable housing, students from lower-income families, and first-generation students, all of whom deserve to thrive in their academic experience.

Challenging the Notion of Traditional Students

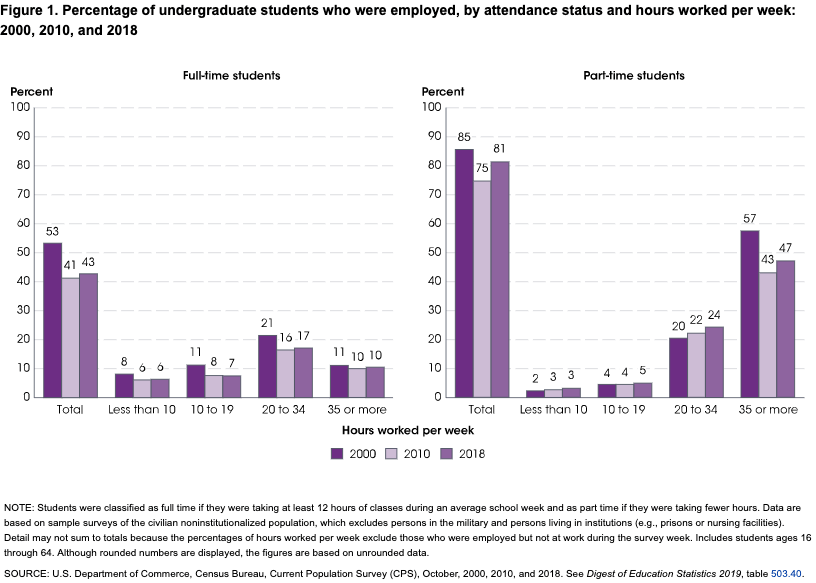

At most universities, the “traditional” college student—who enrolls in college full-time immediately after finishing high school and depends on their parents for financial support rather than working—is the exception rather than the rule. According to the US Government Accountability Office (GAO), in 2016 only about 29 percent of students met this definition; the other 71 percent of students were considered nontraditional due to their financial independence, part-time enrollment, and/or full-time employment. In 2018, 43 percent of full-time undergraduates and 81 percent of part-time students worked at least part of the week, as shown in the chart below. In 2015–2016, an estimated 22 percent of undergraduates (4.3 million of 19.5 million) were parents, according to a 2019 GAO report on student parents.

Christel Perkins, EdD, deputy executive director of USU and assistant vice president of APLU, generously spoke with me about the report. Perkins pointed out that at some urban-serving universities, adults who work to support families are the traditional students. Further, the conversation about traditional and nontraditional students leaves graduate students and international students out of the discussion; both groups are more likely to pay full tuition and receive less student aid and fewer services.

Federal Student Aid Is Insufficient

Title IV of the Higher Education Act (HEA) authorizes the primary federal student-aid programs that support postsecondary students and their families. This section focuses on needs-based programs that provide direct federal support to students and therefore may be used for food and other basic needs:

- Federal Pell Grant Program is the largest needs-based federal aid program for college students in the US.

- Federal Work-Study (FWS) Program is a campus-based aid program providing part-time employment to undergraduate and graduate students. The Consolidated Appropriations Act made it so that students who are eligible for FWS are also eligible for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

- Federal Supplemental Education Opportunity Grant (FSEOG) Program is a campus-based aid program for undergraduates; the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act allowed institutes of higher education to use these funds for emergency student aid.

- William D. Ford Federal Direct Loan (Direct Loan) Program is the primary source of federal student loans.

Federal student aid programs do not cover the full cost of college attendance for many students, in part because the costs of attending college have increased faster than federal and state aid. For instance, in the 2018–2019 school year, the price of attendance for a full-time student attending a four-year public undergraduate institution was $13,900. Meanwhile, the maximum amount of Pell Grants, the largest federal source of needs-based student aid in the US, is $6,495 per year. Recent data revealed that students who have a Pell Grant are more likely (66 percent) to use federal loans over all degree types than students who had not received a Pell Grant (38 percent), perhaps suggesting that students who receive Pell Grants supplement the funds with other loans.

In the last Congress, a proposal to reauthorize those and other HEA programs, and add provisions that would address college food insecurity, died before it reached the House floor.

Most Students Are Not Eligible for SNAP

Most college students are excluded from receiving benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), the largest food-assistance program in the US. Any student enrolled in an institute of higher education who lives on campus and gets more than half of their meals through a school meal plan is disqualified from SNAP. This is based on a 1980 law preventing college students from receiving SNAP benefits, under the outdated assumption that while a student has a low-income while attending college, they are likely receiving financial support from their families.

A 2018 GAO report estimated that about two million at-risk students who may be eligible for SNAP did not participate in 2016. While some colleges have programs to identify and support potentially eligible students in navigating application and enrollment for SNAP and other aid programs, the confusing eligibility requirements and decentralized nature of administering the program create barriers.

Policy Changes during COVID-19 Are Temporary

The US Department of Education recently released $3.2 billion in emergency relief funds specifically to support students at historic and under-resourced institutions. These funds are authorized by the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund (HEERF), which has allocated more than $76 billion available to colleges and universities. As indicated below, Congress authorized HEERF to allow institutions of higher education (IHEs) to “provide emergency financial aid grants to students for expense related to the disruption of campus operations due to coronavirus (including eligible expenses under a student’s cost of attendance, such as food, housing, course materials, technology, health care, and child care).” The table below summarizes HEERF authorizations and other policy changes made by Congress during COVID-19 that directly affect college students. Perhaps the most critical takeaway is that this funding is authorized for emergency use, and should be thought of as a one-time infusion rather than a sustainable investment in basic student needs.

Law |

Policies Affecting College Students |

Enacted |

||

| American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (P.L. 117-2) |

|

March 11, 2021 | ||

| Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 (P.L. 116-260) |

|

December 27, 2020 | ||

| Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act; P.L. 116-136) |

|

March 27, 2020 | ||

| Families First Coronavirus Response Act (P.L. 116-127) |

|

March 18, 2020 |

* The two new exemptions are for students with expected family income of zero, including students who are eligible for a maximum Pell Grant, or students who are eligible to participate in work-study programs (regardless of whether the student actually participates in work-study). A student’s college or university makes this eligibility determination.

Advocacy Opportunities

Appropriations

Congress is presently preparing 12 bills that will fund the federal government in the next fiscal year as part of the annual appropriations process. To date, the House of Representatives has advanced a “minibus” of seven appropriations bills for FY 2022, including the Labor–Health and Human Services–Education bill, which includes $8 million for a pilot Basic Needs Grant. The grants would be prioritized for students at institutions with 25 percent or higher Pell enrollment, and for minority-serving institutions. Funding may be used for programs that provide basic needs to students, or programs that conduct outreach and enrollment support for students. In describing the pilot, the House Appropriations Committee recognized that college and graduate students who are unable to meet such basic needs as food, transportation, housing, and health services are unable to achieve academic success.

The committee also recommended the following increases to federal student aid programs: $1.028 billion for the Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grants (FSEOG), an increase of $148 million over the FY 2021 enacted level and FY 2022 budget request; $1.434 billion for the Federal-Work Study program; and the $400 increase in the maximum Pell Grant that is in line with President Biden’s budget request.

On July 23, ARL signed onto a letter by the American Council on Education (ACE) in support of the minibus.

Budget Reconciliation

The US Senate passed a budget reconciliation bill and accompanying framework that is intended to pave the way for new spending on domestic social policy priorities, including education costs as well as basic needs. Key committees are now drafting bills to operationalize the top-line spending figures and policy priorities included in the resolution. For education, those priorities include universal pre-K for three- and four-year-olds; tuition-free community college; investments in historically Black colleges and universities, minority-serving universities, Hispanic-serving institutions, tribal colleges and universities, and Alaskan Native– or Native Hawaiian–serving institutions; increasing the maximum Pell Grant award; school infrastructure, student success grants, and educator investments; and child nutrition. ARL will work with ACE throughout the fall to track details on these bills, and to support their passage.

#DoublePell

Nearly 1,200 organizations, including almost 900 universities, have urged Congress to double the maximum Pell Grant, which is currently $6,495 per year. According to the Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education, the maximum federal Pell Grant covers just 25 percent of average college costs in 2018–2019, down from 68 percent in 1975–1976. Recent data released by the Pell Institute reveals that low-income and nontraditional students are in less-resourced institutions, and that the debt burden falls disproportionately on nontraditional students, low-income students, and students of color. The #DoublePell campaign began with a letter to members of Congress, noting that Pell Grant recipients are more likely to have student loans than non-Pell recipients.

The appropriations process underway in Congress, and the budget reconciliation package, are potential ways that Pell Grants could be increased; as discussed above, the appropriations bill includes a $400 increase in the maximum Pell Grant amount. Additionally, the recently introduced Pell Grant Preservation and Expansion Act would double Pell by the 2027–2028 school year. In July, the House Education & Labor Committee held a hearing on the bill, in which Chairman Bobby Scott (D-VA) highlighted the diminishing purchasing power of Pell, and its critical role in supporting students from low-income backgrounds to achieve academic success. Recently, ARL joined the #DoublePell campaign, on the recommendation of ARL’s Advocacy and Public Policy Committee.

Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) Simplification Act

Students must complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) to access federal student-aid programs. The Department of Education uses information that students provide through FAFSA to calculate a student’s expected family contribution (EFC), the amount of financial resources that students and their families will use to meet the cost of attendance (COA); EFC and COA are key pieces of information in determining a student’s aid amount.

As noted in the table above, Congress passed the FAFSA Simplification Act of 2019 as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, to simplify access to Pell Grants. The law will guarantee Pell Grants to students with family incomes below a certain amount, reduce the number of questions students must fill out, and simplify the formula for calculating Pell Grant eligibility. The Education Department will implement these changes in the 2024–2025 school year; the delay is due to issues with decades-old technology. The Urban Institute estimated that under this change, most low-income students will automatically receive the maximum Pell Grant. According to the Urban Institute, 76 percent of Pell Grant recipients will receive the maximum benefit, up from 60 percent under the current formula.

A recent report by the National College Attainment Network found that FAFSA applications declined in 2021. The report estimated that due to the COVID-19 pandemic, about a quarter million fewer students completed a FAFSA than expected. Declines were greater in schools with higher concentrations of students from low-income backgrounds—the very students who need the most financial support. Biden’s budget proposal includes $195 million to modernize technology and systems used in processing federal financial aid.

Student Food Security Act of 2021

The Student Food Security Act of 2021 would codify the temporary eligibility change under the Consolidated Appropriations Act, permanently making college students eligible for SNAP.

It would also create a college student food insecurity demonstration program that would allow college students to use their SNAP benefits to purchase prepared food on campus. Finally, if passed, the bill would authorize $5 million in grants to support basic student needs, such as food and housing.

Improved data-sharing can help the federal government and college administrators support outreach and enrollment among students who may be eligible for SNAP. The Student Food Security Act would add questions on student food insecurity to the National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS), which provides information on tuition, living expenses, and student aid. The bill would require federal agencies to create a data-sharing agreement to identify students who have applied for federal financial aid, as well as sending students information on potential eligibility for assistance/application for SNAP and other programs. The Department of Education would be required to notify students who may be eligible for federal assistance based on their FAFSA application.

Campus Resources

While this impact story is focused on policy and advocacy, college students in need cannot wait for Congress to act. Below is a list of resources that can be used by campus libraries and other leaders and administrators to provide real-time assistance to students:

- College & University Food Bank Alliance

- College Student Hunger Statistics and Research, Feeding America

- Empty Shelves: How Your Academic Library Can Address Food Insecurity, College & Research Libraries News

- Food Insecurity at Urban Universities, Coalition of Urban Serving Universities and Association of Public and Land-grant Universities

- SNAP for Students, US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service